Biography

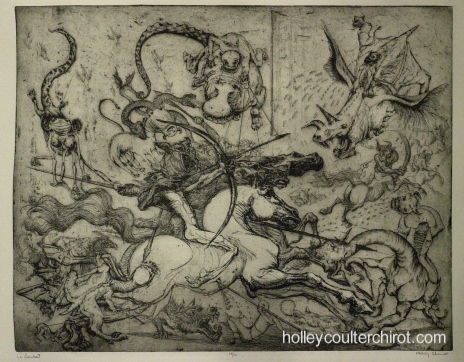

of La Cantatrice.

Etching

To know Holley Coulter Chirot was to add an extra dimension to one's existence, such was her zest and curiosity for life. Intelligent, charming, she was a good companion with a warm personality, a wonderful sense of humour and a delicious sense of the absurd. A talented graphic artist with an unusually vivid imagination, she expressed herself through the traditional media of oil painting, watercolour and sculpture, but also via the decorative arts. In addition to decorating table tops, and making lampstands she made handsome masks. Her main passions were however printmaking, particularly etching and lithography as well as sculpture, albeit of an unusual type, which took the form of animated automats.

of La Cantatrice.

Etching

Holley Coulter was born in Washington on 10 October 1942, to Eliot Brewster and Elizabeth Clark Coulter, the second of four children. The family was raised in a suburb of Arlington (Va) where her father worked for the State Department. Until the age of twelve, all the children attended a private progressive school that their parents had helped found. Her younger sister Jean Brown, née Coulter recalled that their early schooling was a happy time for the siblings, for the school was on a farm complete with barnyard animals and was surrounded by woods. Holley early developed a lifelong passion for animals, particularly horses, learned to ride and revelled in the company of the equines which are a recurrent theme in her art.

In spite of an seemingly idyllic childhood however, the artist's sister recalled that the ambience within the family home was fraught and tense. Holley developed a particularly conflictual relationship with her mother. After attending high school at the St. Agnes Episcopal School for girls in Alexandria (Va) at the age of fifteen she was sent to spend a year at school in Switzerland where she learned French. Summers spent at the family home in Chocorua (NH) alleviated the banality of life in suburbia, which Holley abhorred. A psychoanalyst would theorise that Holley's need to escape into a fantasy world and exorcise her hidden demons through the medium of art may have arisen from her relations with her mother, a relationship compounded by guilt when the latter committed suicide in particularly tragic circumstances when Holley was twenty-one.

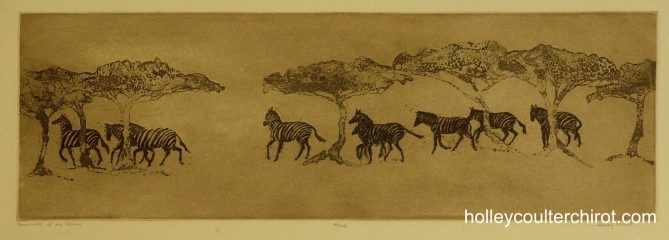

Into Africa:

Etching

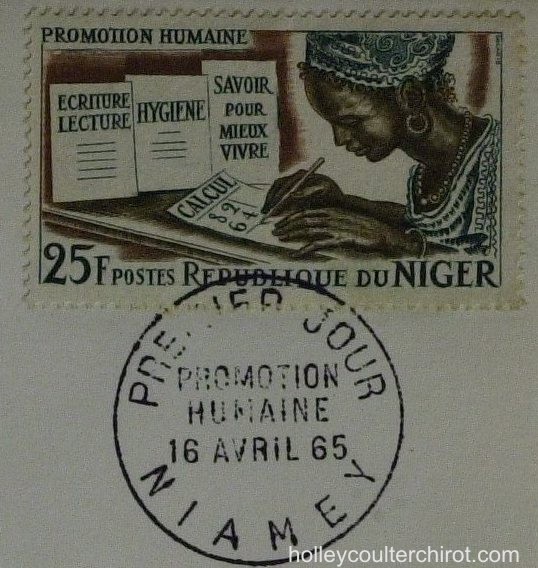

Shortly after graduating from Smith College with a Bachelor of Arts degree, Holley and her future husband Daniel Chirot enrolled as volunteers in the Peace Corps. They were posted to Niger where Holley worked for the adult literacy program in Niamey, and wrote the booklets used as a method for teaching adults how to read in the Hausa, Djerma (Songhay), Fulani (Fulfulde or Peul), Kanuri and Tamasha (Tuareg) tongues. She wrote out the booklets longhand, since at the time there was no printing facility in Niamey equipped with the characters required for block printing. The booklets were illustrated with drawings inspired by Touareg folk tales, which she learned during visits to nomad camps in the desert.

Four of these drawings devoted to the themes of literacy and sanitation appeared on the first stamps issued after independence and are now on display at the Niamey Museum (her work is not however credited). She was befriended by many Africans and drew pastel portraits of them, including the then president of Niger, Hamani Diori. Here, in Africa, she was at last able to realise a long-held dream and acquire her own horse. One of her favourite pastimes was riding with Daniel in the vicinity of Niamey, then less developed than it is now. Holley loved Africa and together with her childhood, these experiences profoundly marked her work. Her prints frequently feature surrealist desert-like spaces haunted by mythical creatures, half man, half beast. (Her favourite novel was Tolkien's Lord of the Rings).

Independence Day,

Niger, 16 April 1965

For example, the print entitled The Island of Sultry Reckoning (in the portfolio Islands), depicts dinosaurs mounted on bicycles hunting sacred treasure on the Isle of Froel, where horses shipped there on rafts are sold into slavery. She later made a series of masks which have a strong African flavour to them.

Mastery of Graphic Art:

After their return to America in 1966 and subsequent marriage, the couple settled in Manhattan. While Chirot completed his PhD, Holley enrolled at the Pratt Institute, where she trained in the graphic arts under professor Murray Zimiles.

With Marcel Chirnoaga.

Etching

She also worked at the Cooper Union printmaking workshop. Early in 1970 the couple left together for Bucharest, in order for Daniel to complete the research for his thesis on Romanian social history. There, Holley devoted her time to painting, sketching and lithography, learned to speak fluent Rumanian and became an honorary member of the Rumanian Union of Plastic Artists. She also collected the local folk art, the source of inspiration for the table tops decorated in the tempera technique and briefly entered a Rumanian nunnery, where she learned to weave kilims. Among the durable friendships she made in Rumania, was with the artist Marcel Chirnoaga, who became her mentor. The relationship, albeit tempestuous, contributed to her personal development and helped her to achieve full maturity as an artist.

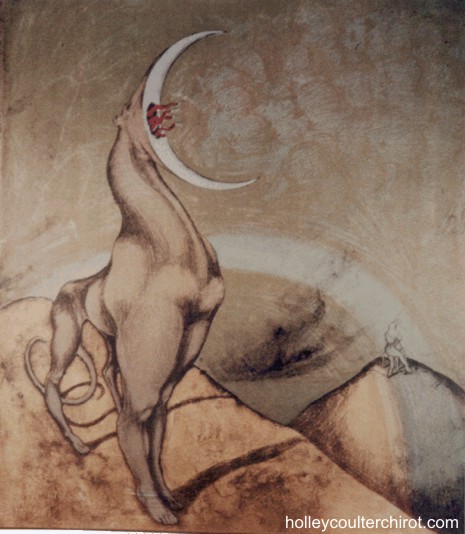

Lithograph

Two things immediately strike us when we regard Holley's work: the astonishing range of disciplines that she mastered and the vividness of her imagination. Haunted by hallucinatory dreams, her work often features a mythical Bosch-like bestiary, half animal, half human, engaged in acts which range from the whimsical to the cruel or the macabre. If it were not for a certain unity of style, one would question whether these works were created by the same artist. A series of coloured lithographs devoted to the circus, including Solmu's Serendipity and See the Prehistoric Lady on a Swing reveal a whimsical joie-de-vivre which corresponds to Holley's joyful exterior persona as I remember her. But her work arouses at the same time a disquieting feeling of malaise, in which the themes of anguish, violence and solitude and an obsession with death are revelatory of her inner demons. How not to be appalled, yet at the same time amused, by the hallucinatory scene depicted in the lithograph entitled the Kiwanis Club Dinner at Mt. Whittier. At the banquet, the guests, part human, part ghoul, part beast, are devouring their repast with rapacius self-interest, a sly dig perhaps at the activities of business and philanthropic clubs.

A Papier Mâché Menagerie:

In January 1971, she and Daniel returned to the United States, only to separate a few months later. In December of that year, Holley moved to France, which she thereafter made her permanent home. In Paris, she worked at the print workshop, Atelier Sauve qui Peut, run by the artist Tristan Bastit, before establishing her own studio, the Atelier Bicéphale with Charles Gancel. In the spring, she would set off for the south of France and work in the Atelier Pousse Caillou, Luc and Perlette Valdelièvre's workshop in Roquefort (Corbières).

Etching

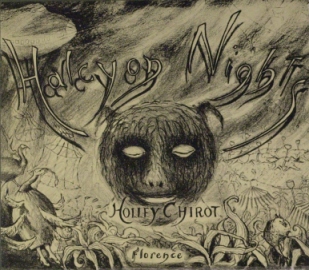

While she lived in France, Holley exhibited her work in numerous European galleries, published eight volumes of original etchings in limited editions, including: Trajet; Petit hallucinatoire (text by Thieri Foulc); Un chant dans le désert; An Incidental Allegory and Cases and a volume of original lithographs, Halycon Nights, in addition to illustrating books of poetry and short stories. From about 1980, she made Sainte-Colombe-sur-l'Hers (Aude) her permanent home, where she was joined by her companion, the sculptor Nicolae "Moni" Fleissig, with whom she lived for the remainder of her short life.

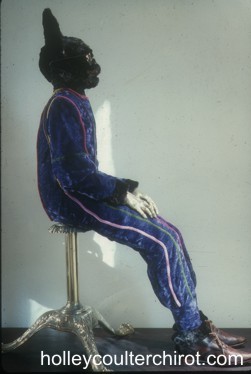

Made from papier mâché, La Cantatrice (1978) had a cumbrous body daintily yet pathetically perched on tiny feet encased in a fragile pair of shoes acquired at the Levallois-Perret fleamarket. But La Cantarice was no ordinary sculpture. She was an automat, complete with mobile beak and flapping wings, made with the advice of a specialist attached to the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers. A tape hidden in the sculpture's innards allowed La Cantatrice to fulfil her mournful destiny as an opera singer. How, one wonders, did she conceive such an extraordinary means of expression? Again, this idea germinated in a fantasy which harked back to her childhood, namely her Christmas presents to her mother. Prepared weeks in advance, in great secrecy, they consisted of life-size papier mâché animals, the first a bright green crocodile and the second a giant tortoise.

The bulky presence of La Cantatrice (also known as The Opera Singer) in the tiny apartment Holley and I shared in Levallois spawned a series of ancillary creations: sculpted clay figurines, watercolours, engravings, lithographs, and a book. A portfolio of engravings, each bearing a quotation from the Bible and prefaced by a poem by Charles Gancel, Un chant dans le désert recounts the lonely and pathetic fate of the creature half-bird, half-woman. The birth of this strange child was followed by many more, all half-man, half-beast : The Unicyclist; Maptut and Soyo, among others. Unlike most artists, Holley did not resort to models, and in her sculptures the face and body used are invariably her own.

Shortly before her death, Holley Chirot made a film entitled Trajet Intime. Shot in colour and black and white, with musical accompaniment by the composer Edmundo Vasquez, the film invites the outsider into a personal and intimate glimpse into the phantasmagorical world of the artist. It was made only just in time, for in July 1984, during a visit to New York with her friend Nicolae Fleissig, this unusually talented and imaginative artist was struck down, at the untimely age of forty-two, by a brain haemorrhage from which she never recovered.

The artist's work has been acquired by American and European institutions for their permanent collections. The Smith College of Art, Northampton (Mass) recently acquired the portfolio Islands. The New York Public Library, the Benjamin Bernstein Foundation, Philadelphia (Pa), the Springfield Museum (Mass.) own collections of prints; as do the Bibliothèque Nationale and the Préfecture de Police in Paris, the Bibliothèque Nationale in Luxembourg, the Intergrafik, Berlin, the National Museum of Rumania and the Ministry of Culture, Budapest, among others.

Susan Day